Irish Anti-Colonial Pride on St. Patrick's Day

March 17 is a good time to remember the powerful solidarity that once existed among the peoples of the world fighting for freedom and against imperialist oppression and capitalist exploitation.

Years ago, when I was in my early 20s, I got pulled over by a big Irish cop somewhere in North Jersey, where I grew up. I was with my wife, and we had our baby daughter in the backseat (we had a playpen rigged up to go across the seats with front legs extended on the floor so the baby could just roll around while we drove).

As the officer got out of his car, we braced for the worst. Nothing about that car was legal. It was a big, beat-up old boat of a Dodge—it used to scrape along the brick walls between the two tenements when we parked it behind our building in the old Italian neighborhood on Pine Street in Montclair.

As the cop was walking over, he stopped to look at the back of the car. He might have been looking at the license plate—but it occurred to me that what might be worse for us than the old illegal car with this reactionary-looking cop was the collection of colorful bumper stickers I had plastered across the back bumper.

Each reflected an anti-colonial cause we’d become active in supporting, mostly by attending demonstrations and marches, sometimes concerts, in New York City at the United Nations or in Times Square, in Central Park, or in front of embassies and missions. We were very cool.

I remember those bumper stickers well. I read them for the last time just a few weeks later when we abandoned the car on the street after it caught on fire. That night I had to hop the fence at the pound where the car was towed to try to retrieve the playpen. Back then you could strip a car of any identifying tags or numbers. I think I failed to get the playpen, and there was no way to peel off and reuse bumper stickers.

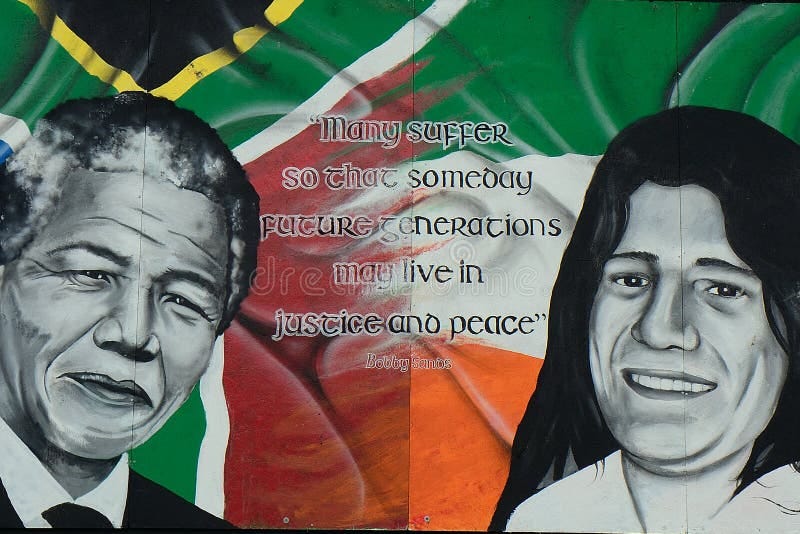

One of the bumper stickers said “US out of El Salvador,” the other “Hands off Nicaragua,” a third “Free Nelson Mandela, and the last one said “Bobby Sands…free at last.” For those who aren’t familiar with Bobby Sands, he was 27 years old and one of the Irish freedom fighters jailed by the British, who went on a hunger strike along with his comrades to protest their treatment as common criminals and not political prisoners. They were confident Margaret Thatcher would give in to the intense international humanitarian pressure before anyone died. Unfortunately, they misjudged the Iron Lady’s bloodthirsty ruthlessness as ten young men starved themselves to death before the strike was called off.

As the big cop waddled over. I rolled down my window, and he just stood there and stared at me. I kept my mouth shut and waited for him to demand my license, registration, and insurance, two of which didn’t exist, and one had been revoked because of parking or speeding tickets—maybe both.

He just gave me a stern look but shook his fat head ever so slightly up and down (not back and forth as was the custom with older, more conservative white men when addressing a long-haired youngster in the 1970s). He looked at me, my wife, and the kid rolling around in the playpen and then just blurted out, “Bobby Sands…eh? Okay. You can go.” We thanked him very politely (as was the custom) and took off driving, very slowly.

I was reminded of this story a few weeks ago while talking to a labor leader in New Jersey about his journey to union activism and eventual leadership. I asked him why he became an organizer. He said, “Believe it or not, I started out as an Irish kid in Brooklyn protesting the British occupation of Northern Ireland.” I told him not only can I believe it, but it’s how I got started too.

We began to reminisce or lament and then grumble about how there was a time in which solidarity between the Irish Republican movement, the South African anti-apartheid movement, the Palestinian liberation movement, the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, the Cuban revolution, the struggle for independence in Angola and Southwest Africa (later Namibia), and many other colonial or neo-colonial movements was bound together by a shared conviction for self-determination and freedom from colonialism, capitalist oppression, and imperialism. I told him I used to go to demonstrations in front of the British consulate with these old, pink-faced Irish guys displaying the rubber bullets that were used to disperse and sometimes blind and even kill young demonstrators. I would then head over to the South African consultant for another demonstration against apartheid and then maybe to the communist bookstore. The old Irish guys didn’t come to the bookstore or the other demonstrations. Like the cop (who knew about Bobby Sands but had no idea who Mandela was), their anti-imperialism didn’t go beyond the Emerald Island, but that was alright—I got out of a ticket.

On this St. Patrick’s Day, let’s remember and renew our shared commitment against oppression, exploitation, and imperialism and raise a glass to Bobby Sands and all those who came before him with a universal vision for freedom, peace, and justice.

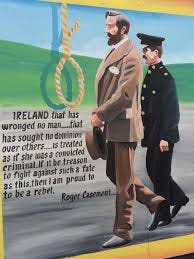

Let's raise a glass to Roger Casement, the Irish diplomat who was radicalized by witnessing the horrors of King Leopold in the Congo. He was hung by the British for trying to deliver German rifles for the 1916 Easter uprising. Among his staunch defenders in the U.S. were Marcus Garvey and W.E.B. Dubois.

Let's raise a glass to Frederick Douglass, who traveled to Ireland in 1845 to raise money, build support, and promote solidarity between Irish freedom fighters and abolitionists in North America. He witnessed the great famine and became a lifelong friend and supporter of the cause of a free Ireland. He was only 27 when he made his first voyage to the British Isles, the same age as Bobby Sands.

Two years later, after Douglass returned from Ireland, Irish American immigrant John Riley formed the St. Patrick's Battalion (or the el Batallón de San Patricio), made up of Irish (and other Catholic) immigrant laborers who defected to the other side in America’s war of conquest against Mexico (an unjust war, manufactured to capture new territory and expand slavery and the power of the slave economy). To this day, the 50 men hung in 1847 is the largest mass execution by the federal government in U.S. history.

Mary Harris Jones (Mother Jones) and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn were both fierce and courageous Irish American labor organizers. Flynn (called the Rebel Girl by the martyred songwriter Joe Hill) was an organizer for the Industrial Workers of the World, or IWW, which supported Irish freedom as part of its international solidarity with working-class people across the globe. James Larkin, the radical Irish labor organizer (and close associate of James Connolly, who would be executed after the 1916 uprising), would come to America and join forces with Flynn to help build a labor-based socialist movement in America.

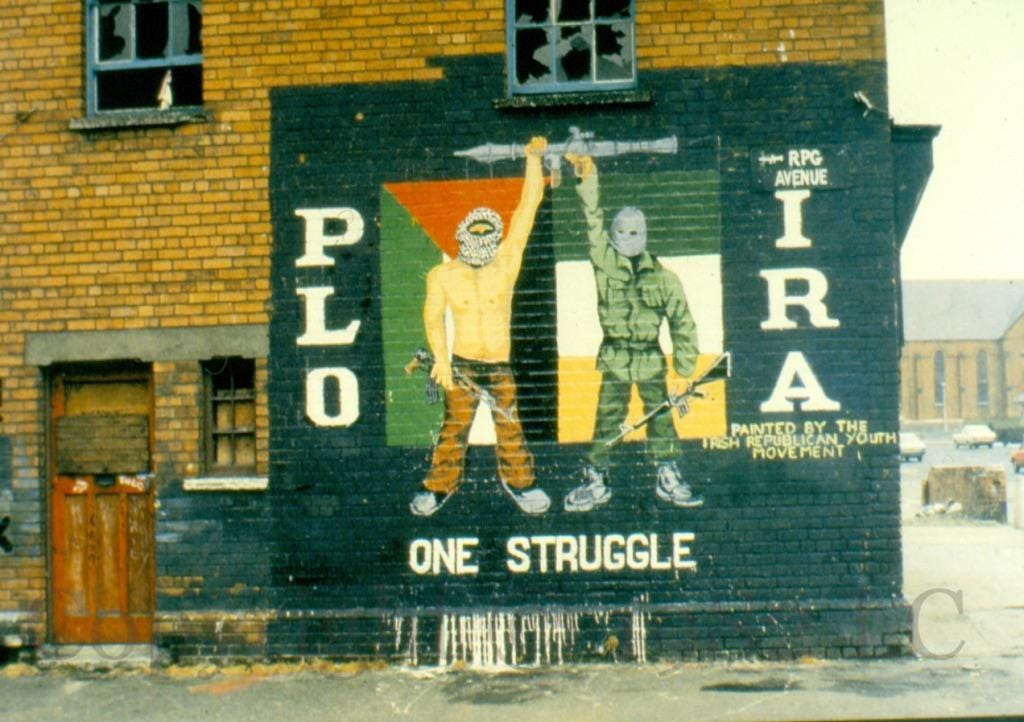

Later in the 20th century, anti-colonial movements were reawakened after the two world wars. In the 1960s, Irish resistance to British rule in the north of Ireland, inspired by Dr. King and the American Civil Rights movement, was met with increased violent repression, including the killing of 13 unarmed civil rights marchers in Derry on Bloody Sunday in 1972. Fellow anti-colonial Irish leaders, Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness, forged strong ties of mutual solidarity and financial support with global freedom fighters, including the African National Congress, the Cuban revolution, the Palestine Liberation Organization, and Colonel Muammar al-Qaddafi’s Libya.

This is why it is not surprising (but another point of Irish pride) that the Republic of Ireland joined South Africa in bringing Israel to the International Court of Justice for their genocidal war on the people of Gaza.

None of this is meant to obscure or excuse the stain of racism in the U.S. perpetrated by Irish Americans and other working-class white immigrant groups and their descendants who were infected with the idea of white supremacy or lured by the promise of privilege and the dangers of solidarity or intimacy with their Black peers and co-workers and neighbors. Frederick Douglass himself was struck by the sharp divergence between his positive experiences in Ireland and when he returned to face the racism of the U.S. “The Irish,” he said, “who, at home, readily sympathize with the oppressed everywhere, are instantly taught when they step upon our soil to hate and despise the Negro.”

Nor is it to draw some kind of moral equivalence between the history of Ireland and any other group or nation’s oppression and exploitation. Such comparisons are a waste of time. Douglass knew well the difference between the horrors and inhumanity of chattel slavery and the wrongs of labor exploitation or imperialist occupation. It didn't stop him from speaking out against all injustice and building solidarity with all oppressed people. W.E.B. Dubois, in describing the “human degradation" of "the white slums of Dublin," wrote that where human oppression exists, there the sympathy of all Black hearts must go.

Like Mahmoud Khalil arrested last week, Jim Larkin, and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, and many other trade unionist and socialist leaders, were arrested for opposing wars, but our government called it treason. Larkin and many other anti-war immigrants in the US were deported.

In the 70s and 80s, there were plenty of Irish Americans (some very conservative and deeply patriotic) who gave far more open support to the outlawed terrorist group called the IRA (or IRA aligned groups) than anything Khalil has said in support of Hamas or the Palestinian cause in general. But there were very few (there were some) who, like my cop friend, made any connection between Irish liberation and the liberation of other current or former European colonies in Latin America, the Middle East, Asia, and Africa.

Perhaps a good example of international solidarity and Irish pride to raise a parting glass to on St. Patrick's Day is Patrice Lumumba, the anticolonial leader of the Congo. It was the atrocities of the Congo’s Belgian colonizers five decades earlier that inspired Roger Casement to turn on the British rulers of Ireland. Lumumba, whose family was Catholic, was named for St. Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland and the expeller of invasive and dangerous foreign snakes.

After his overthrow and assassination orchestrated by the CIA, Fidel Castro sent an Argentinean of Irish descent, Che Guevara (Che Guevara Lynch), to support the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo now fighting a guerrilla war against the government of Sese Seko Mobutu, the U.S. installed dictator. Mobutu was finally overthrown in 1997 by Lumumba’s comrade Laurent Kabila. In the meantime, Lumumba’s children sought refuge in Dublin, Ireland, where his children and grandchildren still reside as citizens of Ireland and members of the African Irish diaspora.